States Can Adopt or Expand Earned Income Tax Credits to Build a Stronger Future Economy

PDF of this report (7pp.)

By Erica

Williams and Michael

Leachman

Updated February 18, 2015 - Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Half of all states plus the District of Columbia have enacted their own

version of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) to help working families

earning low wages meet basic needs. State EITCs build on the success of

the federal credit by keeping working parents on the job and families and

children out of poverty. This important state support also extends the

federal EITCfs well-documented long-term positive effects on children, which in

turn boost the nationfs future economic prospects.

State EITCs provide extensive benefits to children, families, and

communities, and are straightforward to administer and to claim. Lawmakers

in states without their own EITC should consider enacting one. States

that have cut back or eliminated their credits should reverse course, and states

that have limited their credits so that they only offset income taxes

should make them fully refundable, which would vastly enhance their impact.

With this important investment, states can make a big difference in the

lives of low- and moderate-income working families.

Why Consider an EITC?

Many children in working families live in poverty — some 9.9 million

poor children in 2013 had at least one working parent.[1] And many families with incomes modestly above the

federal poverty line, currently about $24,000 for a family of four, also have a

hard time affording basic necessities. A full-time job at the minimum

wage is insufficient to keep a family with one working parent out of poverty,

and sluggish wage growth for low-earning families means that many will likely

continue to struggle.

In addition, low- and moderate-income families in almost all states pay

higher state and local taxes as a share of their income than do upper-income

families. This imbalance results from states relying heavily on sales,

excise, and property taxes, all of which fall more heavily on poorer

families. Some states have become even more reliant on these taxes in

recent years, further increasing taxes on working-poor and near-poor

families.

The EITC originated as a federal tax credit for working people and families

with low and moderate incomes that, among other things, rewards work, reduces

poverty, and improves the outlook for low-income children. State

lawmakers can leverage the proven effectiveness of the federal EITC to address

poverty, low wages, and skewed tax systems by implementing a state-level

credit. Just like the federal EITC, state EITCs:

- Help working families make ends meet. Refundable

EITCs provide low-income workers with a needed income boost that can help

them meet basic needs and pay for the very things that allow them to work,

like child care and transportation.

- Keep families working. EITCs help

families that work get by on low wages, which helps them stay employed.

They are also structured to encourage the lowest-earning families to work

more hours. That extra time and experience in the working world can

translate into better opportunities and higher pay over time. Three out

of five filers who receive the federal credit use it just temporarily — for

just one or two years at a time.[2]

- Reduce poverty, especially among

children. The federal EITC is the

nationfs single most effective tool for reducing poverty among working

families and children. It lifted about 6.2 million people — over half

of them children — out of poverty in 2013. State EITCs build on that

record.

- Have a lasting effect. Low-income children in

families that get additional income through programs like the EITC do better

and go farther in school. And children in low-income families that get

an income boost during their early childhood years work more and earn more as

adults. This is good for communities and the economy because it means

more people and families are on solid ground and fewer need help over the

long haul.

More States Leveraging the Federal Credit, But Others Have Fallen Back

In recent years, three states — Colorado (2013), Connecticut (2011), and

Ohio (2013) — have enacted their own versions of the EITC to bolster the

wages of struggling families,[3] and many other states have improved existing credits.

In 2014, Washington, D.C. became the first jurisdiction to expand the

credit for workers without dependent children in the home, extending the

creditfs reach to childless workers with somewhat higher incomes and setting

its value at 100 percent of the federal credit. Also in 2014, Iowa raised

its credit to 15 percent of the federal EITC from 14 percent, Maryland raised

its credit to 28 percent of the federal EITC from 25 percent (scheduled to

phase in over four years), Minnesota increased in the total value of its credit

by 25 percent, Ohio doubled its credit to 10 percent of the federal EITC

(though it remains nonrefundable), and Rhode Island cut its credit to 10

percent of the federal EITC from 25 percent but also made it fully refundable,

expanding the credit for most households. In 2013, Oregon expanded its credit

to 8 percent of the federal EITC from 6 percent, and Iowa doubled its credit to

14 percent of the federal EITC.

In other states, lawmakers have cut back or eliminated this support for

families earning low wages. In 2013, North Carolina lawmakers allowed the

statefs EITC to end after tax year 2013 and cut it by 10 percent in its final

year. In 2011, Michigan cut its credit by 70 percent and Wisconsin cut

its credit by 21 percent for families with two or more children. Prior to

that, in 2010, New Jersey reduced its credit to 20 percent of the federal EITC,

from 25 percent.

Nevertheless, one in three recipients of the federal EITC now lives in a

state with its own EITC, and state EITCs boost the earnings of working families

by about $3 billion annually.

EITC Design Rewards Working Families

The EITC only goes to working families and is designed to reward their

effort. For families with very low earnings, the dollar amount of the

EITC increases as earnings rise, which encourages families to work more hours

when possible. Working families with children earning up to about $39,000

to $52,000 (depending on marital status and the number of children in the

family) generally can qualify for a state EITC, but the largest benefits go to

families with incomes between about $10,000 and $23,000. Workers without

children can also qualify in most states, but only if their income is below

about $15,000 ($20,000 for a married couple), and the benefit is small.

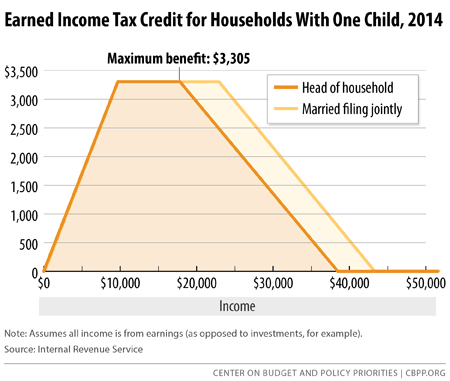

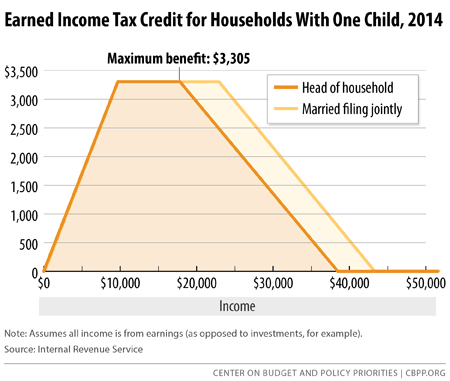

FIGURE 1

The EITCfs design also reflects the reality that larger families face higher

living expenses than smaller families: the maximum benefit varies for families

with one, two, and three or more children. For example, the maximum

federal benefit for families with two children in tax year 2013 is $5,460,

compared to $3,305 for families with one child. (As with most other

federal tax provisions, the IRS adjusts EITC benefit amounts and eligibility

levels each year for inflation.) [4]

Figure 1 shows how the EITC works for a single-mother family with one

child earning the minimum wage in 2014 (about $15,000 a year for full-time,

year-round work). For every dollar she earns, she gets 34 cents in EITC

benefits. The value of the credit continues to increase at that rate

until her earnings reach $9,720. At that point, she receives the maximum

benefit of $3,305. Once her earnings exceed $17,830, the credit shrinks

by about 16 cents for each additional dollar of earnings until reaching zero

(at about $39,000 in earnings).

Most States Model Their EITCs on Federal Credit

Nearly all state EITCs are modeled directly on the federal EITC.

This means that they use federal EITC eligibility rules and offer a state

credit that is a specified percentage of the federal credit. (The

percentages are shown in Table 1.) Minnesota uses federal eligibility

rules, and its credit parallels major elements of the federal structure;

however, it has its own schedule for the income levels at which the credit

phases in and out. Indiana uses old federal guidelines that exclude

recent expansions and improvements to the federal credit. And, Washington,

D.C.fs newly expanded EITC for workers without dependent children will phase in

following federal guidelines, but the maximum credit will extend to 150 percent

of the poverty line (for an individual), and the credit will fully phase out at

twice the poverty line.

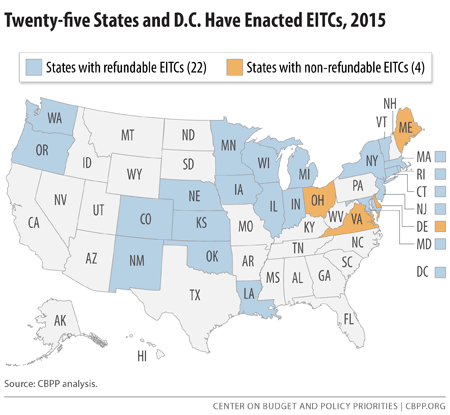

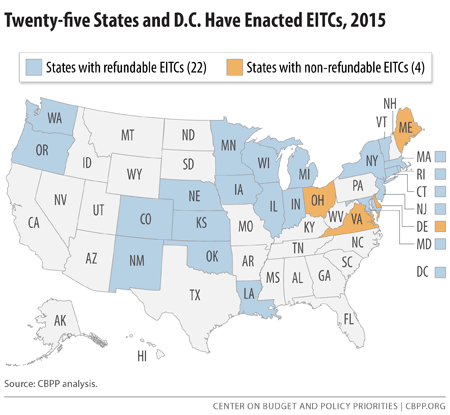

FIGURE 2

Twenty-one states and Washington, D.C. follow the federal practice of

offering a fully grefundableh EITC. (See Figure 2.) In other words,

the amount by which the credit exceeds annual income taxes is paid as a refund;

a family with no income tax liability receives the entire EITC as a refund.

Without it, the EITC would fail to offset the other substantial state and local

taxes families pay. Refundability is what makes the EITC so effective at

reducing poverty, because it lets families keep more of what they earn and

helps them keep working despite low wages.

The remaining four states with EITCs — Delaware, Maine, Ohio, and Virginia —

offer non-refundable credits. That means the credits are available only to

the extent that they offset a familyfs state income tax. A non-refundable

EITC can reduce income taxes for families with state income tax

liability, but it does not make up for other taxes that working families

pay. Nor does it do much, if anything, to help keep families working and

out of poverty. Ohiofs EITC is limited even further, to no more than half

of income taxes owed on taxable income above $20,000.

TABLE 1